Beyond introvert vs. extrovert

It would be hard today to find anyone who hasn't heard about the ideas of introversion and extroversion. Though Carl Jung first defined the concept in the early 1900s, it broke into the mainstream in recent years, being featured on morning news shows, TED talks, and self-help books. Search interest in the topic keeps growing. I've even overheard strangers talking about the idea on the street.

In 2012, Susan Cain released a book on the topic titled Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking. It shot to the top of bestseller lists across the world and stayed there for months. As of last year, four million copies had been sold.

The success was unsurprising. What could be a more obvious home-run than a book extolling the virtues of introverts? Introverts around the world curled up in bed with their cats while nursing cups of tea, feeling validated by Cain's argument that knowing how to shut up is an enormous strength in the modern day. I was one of them.

Ten years passed. All of us, extroverts and introverts, were forced to spend a few years isolated during the pandemic. Some claimed that introverts reveled in the lockdowns. But many "introverts" came to realize that they needed other people, too—perpetual solitude doesn't cut it.

I'm a conceptual person. I believe the ideas we use to think about people greatly impact our ability to understand and accept ourselves and others. But when a concept fails to accurately represent reality, I feel bothered. A clunky concept obscures rather than illuminates.

Now that most people have internalized the binary model of "introvert" vs. "extrovert", I believe we're reaching the limits of this idea's usefulness. The cracks in the dichotomy are starting to show. So why not move beyond it?

Introverts, extroverts... ambiverts??

When Jung wrote about introverts in his book Personality Types in the 1920s, he described an introvert like so:

He holds aloof from external happenings, does not join in, has a distinct dislike of society as soon as he finds himself among too many people. In a large gathering he feels lonely and lost. The more crowded it is, the greater becomes his resistance. He is not in the least "with it," and has no love of enthusiastic get-togethers. He is not a good mixer.

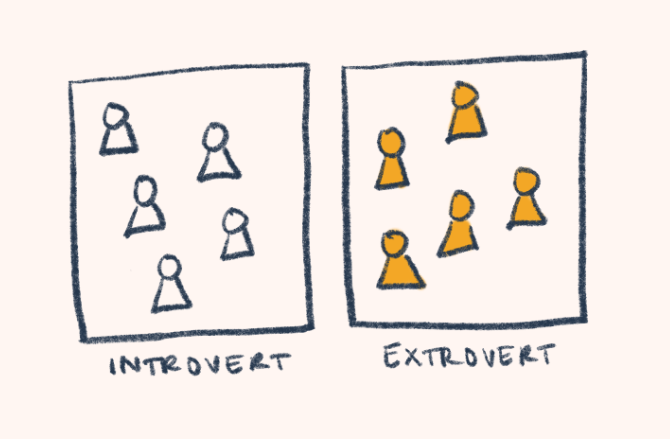

This description set a particular tone. The implicit assumption was that there are only two types of people: introverts and extroverts, and everyone belongs to one of these categories.

But what am I? Most people would describe me as stoic, quiet, thoughtful—even aloof—but I actually do enjoy crowds and "enthusiastic get-togethers." For me, they provide a way to mingle and chat with new and interesting people. Yes, I feel drained by them eventually, but I don't perfectly fit into either of these boxes.

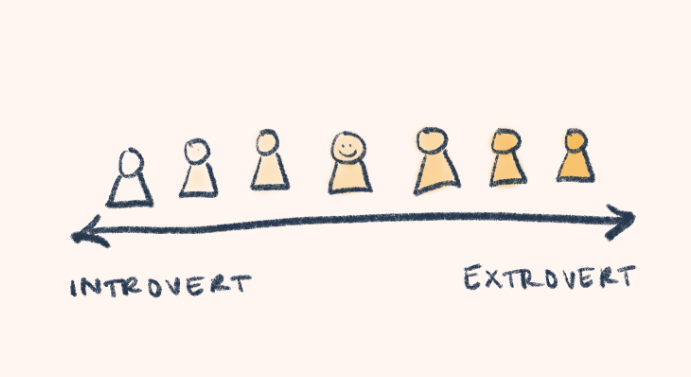

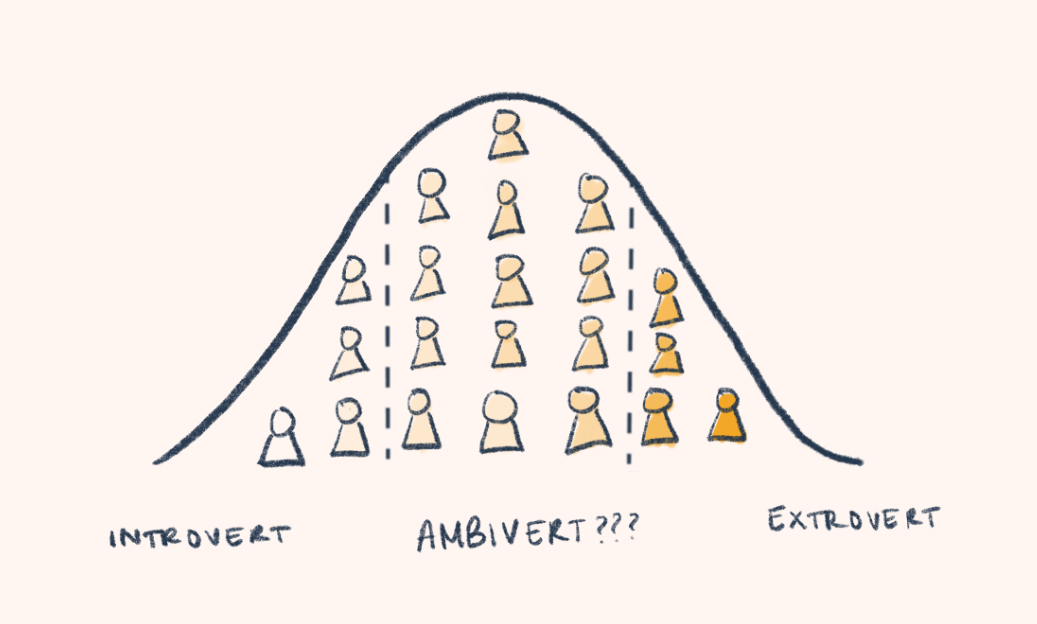

As with any binary model of human categorization, the easy way out of this critique is to present the model as a spectrum—there's a continuous line from introverts on one end to extroverts on the other, and people can belong anywhere along this spectrum. The middle zone is referred to as ambiverts, a new ambiguous category. Problem solved!

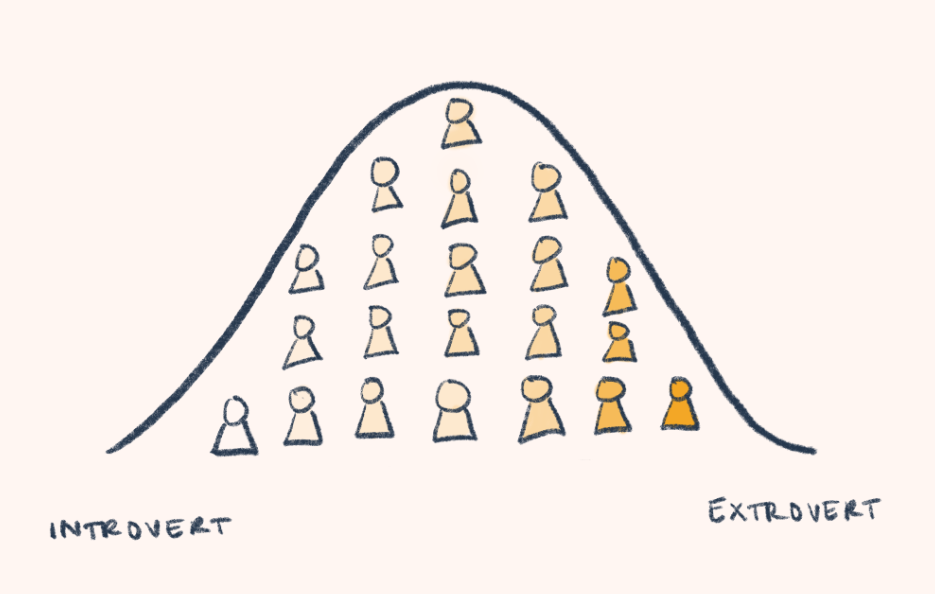

Except... how many people belong on each end of the spectrum? It turns out that like most continuous spectra, most people end up in the middle, roughly following a normal distribution like this.

But this means that most people (roughly two-thirds) are in an ill-defined middle category! This entire introvert/extrovert/ambivert thing just amounts to "most people like to be alone sometimes and around people some other times"?? What's the point?

We need a better mental model for the many of us who are ambiverts. And I think that a more nuanced model could be useful for people who strongly identify as introverts or extroverts, too.

Four states of being

Over the past few years, I started to think about people and how they interact in a new way. What inspired me was the idea that ambiverts are often described as being "circumstantial" in terms of how they interact and behave.

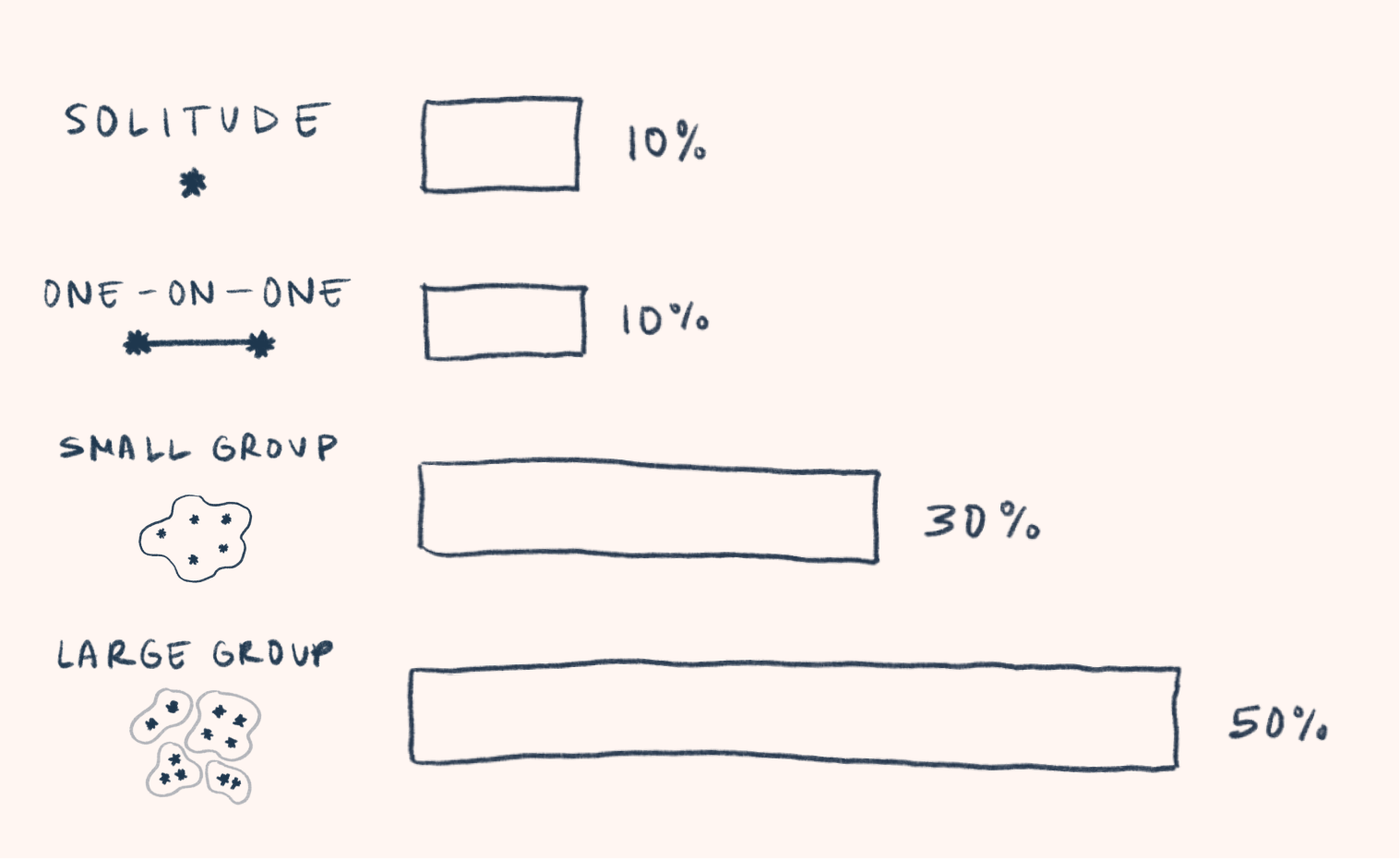

But this begs the question: what are the circumstances I can be in? I thought about it for a while, and settled on four primary states of being I might inhabit at any moment in time:

- Solitude. I'm alone and not interacting with anyone.

- One-on-one. I'm interacting with only one other person, who is vice versa only interacting with me.

- Small group. I'm interacting with three or more people in a single, shared conversation. Because of the structure of conversations, this caps out at about 5-6 people.

- Large group. I'm interacting with many people at once. Because it's nearly impossible to sustain a single conversation among, say, a dozen people, this means that I'm usually navigating through many smaller groups in a large setting.

Each boundary between categories has some conceptual or experimental backing:

- The jump from solitude ("no other people") to interaction ("at least one other person") seems self-evidently different.

- The difference between one-on-one and small group interactions is backed by recent psychological research, which suggests that "group and dyadic conversations are so different [...] that we suggest they should be considered categorically different activities."

- Going from a small group to a large group is just a jump from "one conversation" to "many conversations."

Most importantly, I think that each of these categories feels very different from the others. Allow me to elaborate on each one for a moment...

As I write this blog post, I'm sitting at my desk in solitude. No wonder—it's nearly impossible to write while interacting with someone else or with a group of people. Solitude is the act of engaging in conversation with yourself, or perhaps broadly with the world but without expecting any answers back. Your stream of consciousness flows without obstacle; you observe more; you let things unfold.

In the modern day, the cacophony of group interaction that occurs in messages, DMs, group texts, and social media has the effect of rendering solitude an increasingly rare luxury. When we're away from our devices, we feel cut off from the world. If we resist the impulse to constantly plug ourselves back in, we sometimes find that solitude is when thoughts arise from the unconscious, unbidden. Opening ourselves up to them is crucial, I think—or at least, it's crucial for me.

Plenty of people live alone these days. For them, solitude may feel like something to avoid, a lonely state of being that they hope will end sometime, once they find partners and friends and family. But everything needs moderation, and connecting with others is no exception.

Solitude is a salve in a hyperconnected world.

A curious thing happens when precisely two people interact for an extended period of time. Typically, only one person can speak at a time, so the other person has to listen. The two take turns. Maybe one person is extra talkative and dominates (or "carries the conversation"). Maybe one person mostly listens.

What's unique to a one-on-one interaction is that it's rife with expectations. If I'm talking to you, I expect you to listen attentively and understand what I'm saying; and you expect the same from me. This can lead to a feeling of being constantly observed, which some people may dislike.

But having someone pay attention to you, when it's genuine and desired, can feel deeply rewarding, too. That sort of attention has a way of dissolving boundaries, causing people to gradually open up about things they may be hesitant to reveal: fears, hurts, sorrows, self-doubts, insecurities. Having one other person absorb, mirror, and modulate these negative feelings provides a sense of connection most people need.

I've rarely seen people open up and share difficult experiences in small or large groups. And there is some merit to dealing with problems in solitude, but there are limits to going it alone.

One-on-one interactions are the essence of healing and deepening—they're how weak ties become stronger ones.

Something I suspect many people crave in a modern, atomized world is a greater sense of community. But what is community? It's little more than repeated, spontaneous interactions of groups of people over time.

A small group is a group of people that can engage in one prolonged conversation. I define it as a group between three to six people (sometimes seven, if a few are very quiet). Maybe they're sitting around a table and talking for a while, perhaps for thirty minutes or more.

In contrast with a one-on-one interaction, a small group is more forgiving and accommodating in terms of interpersonal expectations. If I'm hanging out with three friends, it's totally acceptable for me to be quiet, and mostly listen and observe. Many people labeled as "introverts" can love a small group interaction—it provides opportunities for them to chime in when they wish.

The dynamic between members of the same group can fluctuate over time. Let's say that I meet up with a few friends at a diner every week. This week, a friend is energetic and fun; he does most of the talking. Next week, he's exhausted; he mostly listens. Either way, the group dynamic can absorb his emotional state and give back to him what he needs.

Small group dynamics are extremely fragile. One person leaving the group can permanently change the nature of things, and it takes time for a dynamic to develop among a group.

At the same time, there are moments when a group interacts for the first time and things just feel right, like a dynamic that was always meant to be. Those moments are worth paying attention to: they are the seeds of community.

A single conversation can only be so big. I've noticed that when a group reaches a size of about six or seven, the group tends to splinter into multiple parallel conversations. Maybe it's because of the physical constraints of how many people you can sit next to or hear. Whatever causes it, once you have more than seven or so people in a room, you're now part of a large group.

A large group is one in which many conversations are happening simultaneously. Conversations emerge and die out spontaneously as people chat with each other. There's a fluidity to everything—you start chatting with someone next to you, someone nearby overhears and joins the conversation, then the conversation dissolves, only to coalesce again later.

While a small group interaction might happen around a table, a larger group interaction feels more natural standing up. This enables fluidity as the group continually reconfigures itself. Next time you go to a gathering, notice how the first few guests naturally sit around a table, then transition to standing right around when the seventh or eighth people arrive.

The fluidity of large group interaction feels even more dynamic than the give-and-take of a small group. But the rules of how to enter, exit, and navigate conversations can be confusing, and the fluidity makes it difficult to have a prolonged conversation that gets into anything deep or heavy. This is probably why "introverts" find large groups draining—making your way through a crowd requires assertiveness and expressiveness, and if the conversations aren't even intimate or deep, what's the point?

The beauty of large groups is their unpredictability: you might end up interacting with someone you never expected to meet. That experience might open up new possibilities in your life. Even if it doesn't, the spontaneity of a crowd of strangers is simply a fun time, if you enjoy novelty and dynamism.

Interaction profiles

So how can you use these ideas to actually live a better life?

Start by reflecting on how much time you think you'd ideally spend in each state of being. How much do you value solitude? How much do you want to be interacting with close friends or loved ones one-on-one? How much do you like small gatherings, or big parties? Allocate a percentage for each of them, out of 100.

A hypothetical "extroverted" interaction profile

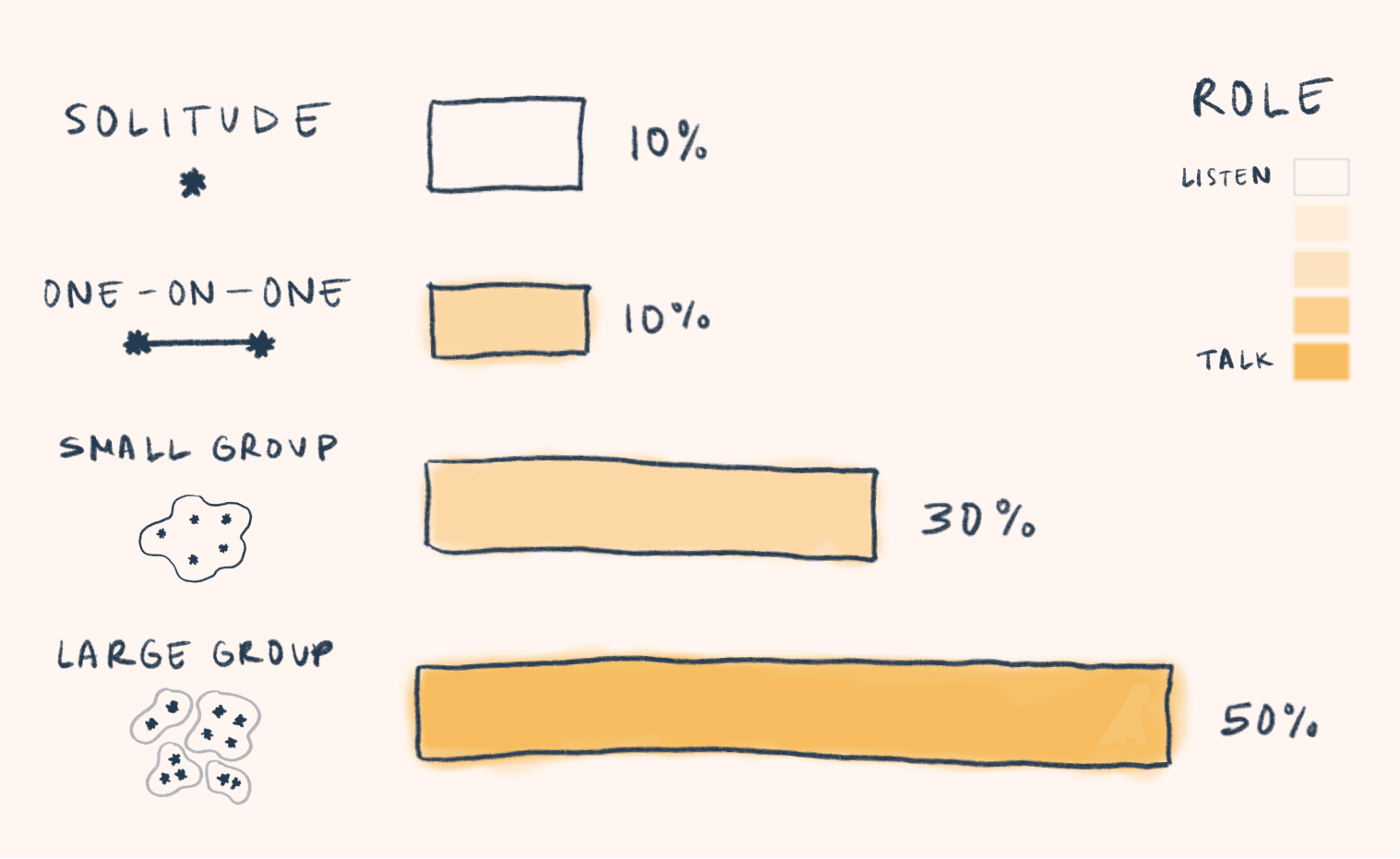

A hypothetical "extroverted" interaction profileNext, consider what your ideal role is in each non-solitude setting. For example, some people enjoy being mostly talkative in one-on-one interactions, but actually get pretty quiet when there are four or more people in a conversation; some people are the other way. Do you want to be the talkative one or the listener in your one-on-one friendships, small groups, and large groups?

Solitude is, of course, purely listening... or is there a way to "talk" in solitude? Perhaps by writing a blog post?

Solitude is, of course, purely listening... or is there a way to "talk" in solitude? Perhaps by writing a blog post?Together, these questions make up what I'll call your interaction profile—a summary of your ideal balance. When you deviate from it, you'll probably feel frustrated or just off in some way.

Now, to make use of all this, think about how your actual life differs from your interaction profile:

- What are you actually spending your time doing? Does it differ from your ideal? Why?

- In each setting, are you able to occupy your ideal role? If not, could you nudge yourself closer to that ideal?

- What about other people in your life who are important to you? Are they getting what they need? Could you be a better friend, partner, or parent to them?

Example: Me

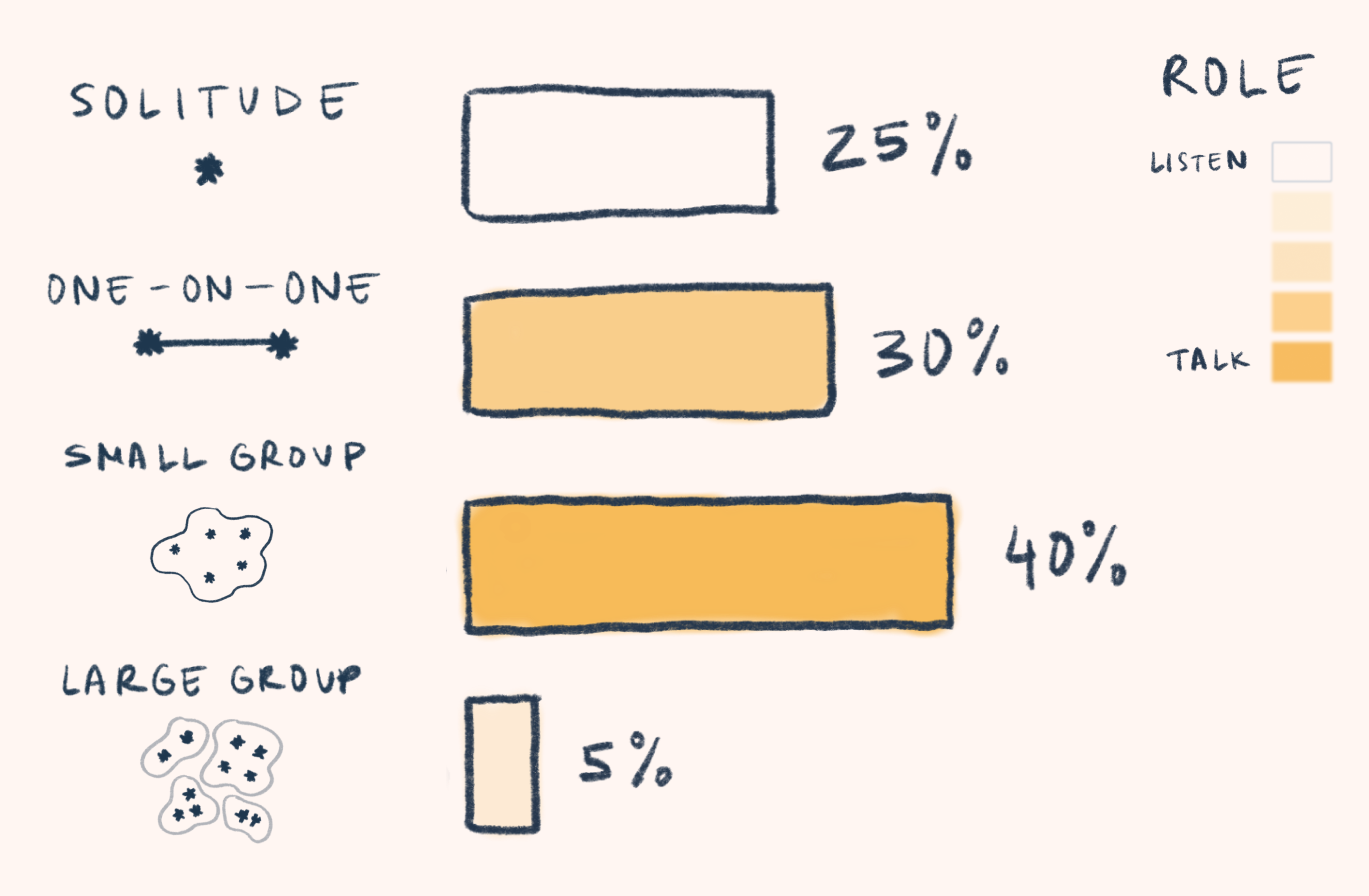

Let me apply this model to myself to paint a picture. I think my ideal interaction profile looks something like this:

- 25% solitude. I love sitting with my own stream of consciousness for a few hours at a time, thinking about ideas, and getting into a flow state.

- 30% one-on-one, balanced role. I enjoy deepening close friendships and getting to a greater level of emotional depth with a few friends, and I like talking and listening about equally.

- 40% small groups, somewhat expressive role. If I could figure out the logistics, I would love to hang out with small groups of friends almost every day. The dynamic that emerges when there are three or more people in a room is refreshing and fun for me, and these are some of my happiest times. I'm a little more talkative in small groups.

- 5% large groups, observant role. This is definitely what I enjoy the least, but I do like going to bigger gatherings every once in a while, and if I never did this, I would be a bit sad. I like meeting totally new people and navigating a crowd, but I'm not that expressive.

Over the years, reflecting on this interaction profile and comparing it with my current life has led me to some insights about myself, many of which I've used to nudge my circumstances in a better direction:

Lacking solitude is really hard for me. On most days, I need a few contiguous hours when I can be in my own head and just read, think, and observe. If I don't get this, something feels deeply wrong, and I feel restless. I need to consistently make time for this aspect of my life.

One-on-one friendships are not enough. In a busy city like New York, it can feel like every social interaction has to be painstakingly arranged between people all the time, and it's always easier to just meet up with one friend at a time. Although these interactions are meaningful and deep, they lack the dynamism of small groups, especially a recurring small group that gets to know each other well. For me, just hanging out with a lot of friends in isolation doesn't cut it.

I want egalitarian one-on-one conversations. In one-on-one conversations, I want to play a balanced role, talking and listening about equally. I've noticed that when people consistently do most of the talking in one-on-one settings, I find myself feeling ignored and frustrated.

I really like small groups of 4-6 people, and enjoy playing a moderately talkative role. I've noticed that in a group of 4-6 people, I'm usually the third-most or fourth-most talkative person, and I really like being in this role. I don't have to carry the conversation or do most of the talking, but I can chime in with reactions, jokes, and stories consistently. Being in a small group of this size regularly makes me happy.

I enjoy large groups, but like to mostly observe and facilitate. Nobody would ever describe me as "the life of the party," but I do like going to large group gatherings once or twice a month, mostly because I like soaking in the vibe and meeting new people. In large groups, I'm mostly an observer, not the primary actor or center of attention. Recently, I've really enjoyed hosting larger gatherings, because it gives me an excuse to enter and leave conversations easily, which makes it easier for me to navigate in a setting where I might usually feel shy.

Of course, these dynamics aren't just true in my personal life—they affect my workplace habits a lot, too. I usually favor written communication and love having big blocks of open time on my calendar, but I also like the bustle of working in an office on small, tight-knit teams.

In fact, I've started to notice that these preferences even carry over into my digital life. I need solitary time away from digital contact; I like maintaining a few close relationships online; I really enjoy participating in a few active group texts; and I heavily avoid posting in digital "large group" settings like social media, but I do enjoy lurking on them. It took me a lot of effort to start this blog, and I still avoid the sheer chaos of mass media sites like Twitter. That probably benefits my mental health, but maybe it holds me back in other ways.

Balance, not "batteries"

One of the things that annoys me most about the introvert/extrovert model is the idea that introverts are "charged" by solitude and "drained" by interaction, while extroverts are the other way around. But for the two-thirds of us who are "ambiverted," what charges or drains us? It's not clear.

I think a better way to think about it is like flavor preferences in food. Some people just like saltier foods than others. Some people have a high spice tolerance. Some people hate bitter foods and love sweetness. There are all sorts of combinations.

Interaction profiles are just like flavor preferences. Every preference is valid, even if someone else's taste might seem horrendous to you! And if you took someone who loves salty food and fed them only salt, they would eventually reach a point where they've just had too much. Interaction preferences are like that: even if you love solitude, there is such a thing as too much solitude. Nobody wants just one thing or the other; you need balance.

More nuance, more understanding

You could read what I wrote about myself above and just say, "This guy is an introvert." I like solitude, I'm observant at parties, and I rarely want to be the person talking the most. But boiling my personality down to this simple categorization obscures the truth. How much time should I be spending doing each of these things? Are my closest relationships actually fulfilling for me? What might I need that I'm missing?

Mental health is a slippery thing. When we're out of balance with what we need, the resulting sense of difficulty and malaise can drive us to do all sorts of things to compensate. We may indulge in habits that are damaging longer-term, or even lash out at those we're close to.

I've sometimes felt completely out of whack at work, in personal relationships, or in life in general. Investing in a foundation of healthy eating, sleep, and exercise is definitely the first thing I need. But after that, I've found that the next most important thing is ensuring that I'm living in harmony with my ideal interaction profile.

You can't live a life that's true to yourself unless you understand yourself. Relying on a hundred-year-old binary classification of human interaction preferences collectively holds us back from that self-understanding, and I believe it's time to move past it.

I hope this mental model helps you as much as it's helped me. Did the idea resonate for you, or lead you to realize something about yourself or someone you're close to? If so, let me know—I'd love to hear from you.

Illustrations graciously provided by the illustrious Emeline Wu. Pun intended.